by Helen Dennis, June 2022 ~

Donald and Jessie McLean were both in their early twenties when they married on Christmas Eve 1852 in the picturesque village of Cawdor in the Scottish Highlands very close to the historic town of Inverness. Cawdor occasionally received a light dusting of snow at Christmas, but the aesthetic qualities of this charming village were not enough to weld the young couple to their Scottish roots.

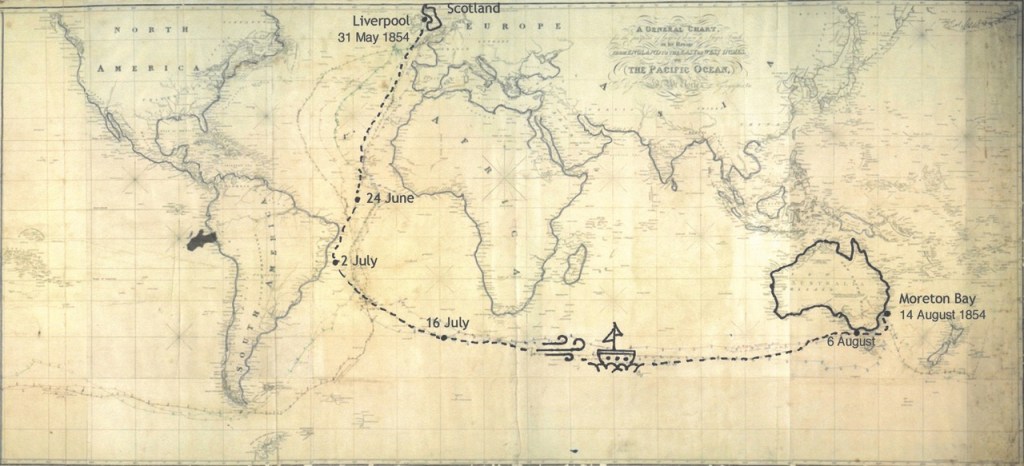

Jessie was pregnant with their first child when, in May 1854, the couple stepped across the gangplank above the murky waters of Liverpool’s River Mersey, onto the sailing ship Genghis Khan, bound for the Australian colonies.

Many Scots emigrated during the 1850s but it wasn’t until 1854 that a significant number chose Australia as their destination. Had they sailed a few years earlier, Donald and Jessie might well have ended their journey a little closer to home, in North America.

Journeying across the globe as assisted immigrants, the newly-married couple left behind a large extended family. While Donald’s background proved largely untraceable, it is known that Jessie’s eight siblings, their families and her parents, all lived close to Cawdor.

Assisted immigrants were selected for their good character and their potential to boost both the labour force, and the population, of the Australian colonies. In Scotland, the industrial revolution and the after effects of the “Highland clearances” – a tumultuous period in which the working classes were evicted from their land – had forced many workers into an ever-diminishing jobs market.

Australia, by contrast, was desperate for workers. Labour shortages caused by the discovery of gold in southern Australia resulted in a vigorous campaign to attract immigrants to the northern districts of New South Wales (now Queensland). Donald and Jessie were among a large group of immigrants from their local area to migrate to the northern port of Moreton Bay in 1854-55.

The Genghis Khan made the trip to Moreton Bay in a record-breaking 75 days but the voyage was likely to have been particularly uncomfortable for Jessie. The usual trials of ocean travel would have been augmented by morning sickness and the limitations in mobility that pregnancy engenders. Many women succumbed to premature labour during long voyages, and many babies were lost at sea. The circumstances surrounding the birth of Jessie’s baby Anne are unclear, but evidence suggests she was born during 1854 and died shortly afterwards.

No definitive birth record exists for Anne. One record that initially looked promising – a baby born in May 1854, and baptised in Brisbane in September that year – has proved inconclusive, as the baby was born prior to the McLeans departure from Liverpool. Many infants were listed as passengers on the Genghis Khan’s passenger list, but Donald and Jessie McLean travelled alone.

The Genghis Khan charted a route that was often battered by gale-force winds. The threat of icebergs in the Southern Ocean made for a perilous voyage. The ship was fitted with fires for cooking and candles for light, creating an ever-present threat of fire on board, especially during times of rough weather.

While sickness was common and disease spread readily in cramped quarters, the McLeans were fortunate to avoid illness, and found themselves among “a well conducted class [of immigrant]”. As the Moreton Bay Courier reported, “a finer body of men could not be seen”.

Upon arrival in Moreton Bay in August 1854, Donald and Jessie would have been required to immediately repay their passage, or enter into a two-year-long indentured employment agreement. Evidence suggests the couple quickly repaid their fare and travelled south, as the following year their second child Thomas was born near Morpeth.

Thomas, like his older sister Anne, was born prior to the introduction of compulsory birth registration (which began in Australia in March 1856). In the absence of official birth records, evidence of the births of Anne and Thomas has been pieced together from their younger siblings’ birth certificates (where “previous issue” is recorded).

By the time the couple’s third child Duncan was born in 1858, Anne had died. The couple subsequently lost three more infant children – Angus, John and Mary. Four of the couple’s eight children survived into adulthood: Thomas, Duncan, another Ann and Elizabeth.

The family settled in Morpeth where they remained for the next 26 years. Morpeth is situated on Australia’s east coast about half way between Sydney and Brisbane. By the 1860s, the importance of Morpeth as a sea port “… was quite the equal of Newcastle, if not exceeding it”. Donald carried on private business for a short time before commencing work as gaoler at nearby Maitland Gaol in 1862.

After 19 years at Maitland Gaol, Donald was promoted and became the first governor of the new gaol at Tamworth. Jessie was appointed Matron of the Tamworth Gaol, a position she held until her death in 1889.

In an era of legislated capital punishment, some aspects of Donald’s job might have been quite challenging. Historically, only five hanging executions have taken place in Tamworth; one of these – an unusual “double” hanging – took place during Donald’s time as governor. The Government Gazette of 1894 rather brutally describes the two felons being “hanged by the neck until their bodies were dead”. By this time hangings were no longer public events, but there was nevertheless a large crowd of officials present, including Donald, as well as a group of local schoolboys who had perched themselves “high up in a white-box tree” outside the gaol walls.

Nowadays, it is difficult to understand the justifications the various religions put forward in favour of capital punishment. In the mid- to late-1850s however, the view that the death penalty was warranted as retribution for certain crimes, was more widely held. Donald and Jessie were Christians who followed the teachings of the Scottish Churches – Presbyterian, and probably also the Scottish Free Church. While witnessing a hanging might be unthinkable to us, during their time the event would have been seen as acceptable.

Jessie died aged 58 and was buried in Tamworth in the Presbyterian portion of the Tamworth cemetery. Her large granite headstone contains a beautiful floral carving set above a lengthy epitaph attesting to the love the family held for her. Poignantly there is space remaining on the headstone; presumably set aside for Donald when the time came.

Six years later, at the age of 61, Donald remarried. Upon his retirement in 1896, Donald and his new wife relocated to Sydney where he lived the remaining twelve years of his life. He is buried at Rookwood Cemetery with his second wife, Catherine, who died in 1923.

At the time of Donald’s death, he was survived by just two of his eight children, Thomas and (the second) Ann. Ann, or “Annie” as she was known, was very close to her father – she worked with him at the Tamworth Gaol, retired at the same time as Donald and also relocated to Sydney. In a newspaper notice published a year after his death, Annie referred to Donald as “a loving and devoted father”.

The only other surviving child Thomas, my great-grandfather, had become estranged from the family following a string of abandoned wives and children (legitimate and otherwise), a bankruptcy and alleged drunken behaviour. Unlike Annie, Thomas was not remembered in Donald’s will, and sadly died alone 23 years later.

Donald and Jessie McLean’s journey from Scotland to Australia was likely undertaken with a degree of both trepidation and hope. Jessie’s resolve may have been tested as early as the first few days on board the Genghis Khan as pregnancy heightened her discomfort during the sea journey.

The trauma of losing baby Anne not long after arriving in Australia, and the long journey south from Brisbane to Morpeth would not have been easy. In addition, the couple had left behind their homeland and a large extended family.

Ultimately however, the McLeans’ decision to escape deteriorating conditions in Scotland provided them with security and stability of employment. Hopefully Donald and Jessie’s quest for greater opportunity resulted in the realisation of their dreams for a brighter future.

[Image: Map of the route taken by the Genghis Khan from Liverpool to Moreton Bay, 31 May to 14 August 1854.]