by Helen Dennis, November 2022 ~

Roughly mown grass covers the ground surrounding a few timeworn graves in a quiet section of Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney. Weeds poke through gravel on the grave of Thomas Maclean’s neighbour. There is no marked grave for Thomas; no headstone. He lies forgotten beneath unruly tufts of kikuyu.

Until recently my family knew little about Thomas; even his name was a mystery. Thomas’ son’s death certificate shows his father’s name as ‘Bruce’. My father Richard Maclean knew instinctively not to ask about his grandfather. He’d heard bits and pieces – rumours – that his grandfather had left the family and died a short time later in Queensland. But he knew not to ask anything more. He understood the family intended that his grandfather remain nameless.

I wondered why Thomas was never spoken of. What had he done to earn the ire of his descendants?

We are fortunate today as researchers to have access to myriad methods and records to trace our ancestry. It was not too difficult to discover that the enigmatic ‘Bruce’ on my grandfather’s death certificate was in fact Thomas Ross Maclean. Thomas has no birth certificate, but evidence of his ‘nascency’ can be gleaned from his siblings’ birth certificates and his mother’s death certificate.

Thomas’ father Donald had begun his working life as a labourer in Scotland. In Australia he’d worked as a shoemaker and nightwatchman, before gaining employment as a gaoler. By the time he’d retired, he’d worked his way up to become the Governor of the Tamworth Gaol. Thomas’ father was a pious man; an active member of the Presbyterian church.

As the eldest child of this hard-working father, Thomas would have been expected to set a good example; to live a devout life, work hard, marry, and have children. Unfortunately, Thomas wasn’t good at any of those things (save, perhaps, the last).

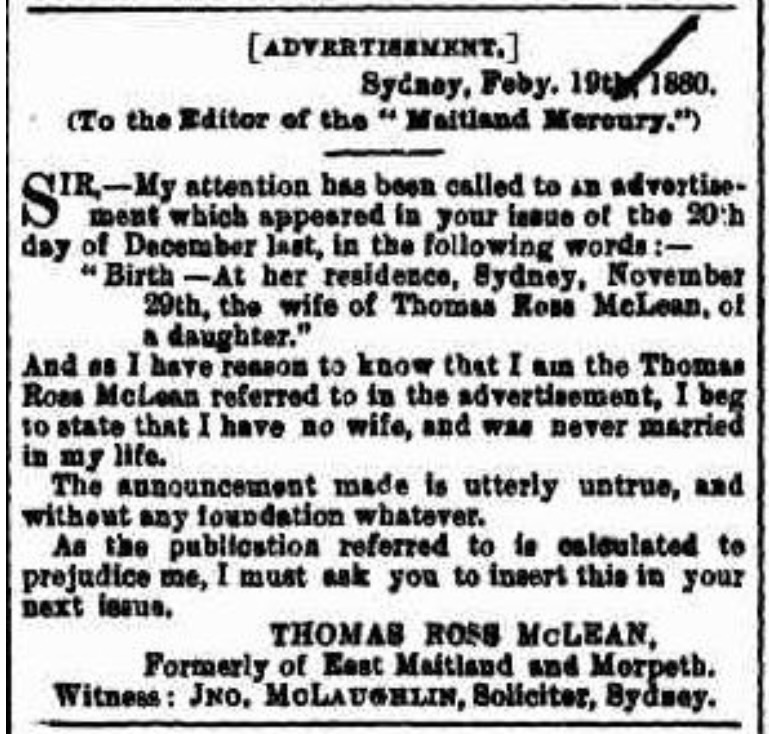

A Maitland Mercury notice from 1880 seems prescient as I read it now. The notice – placed by Thomas – was a refutation of a birth announcement placed a few weeks earlier by a woman who claimed to be his wife. Thomas was not married and denied that he was the child’s father.

Thomas’ refutation of a birth announcement placed in the Maitland Mercury on 20th December 1879, by a woman claiming to be his ‘wife’. Unfortunately, the woman’s original notice has not survived.

Maitland Mercury, 24th February 1880.

Of course, we will never know who was telling the truth – the mother of the child (if there even was a child), or Thomas? Subsequent events in Thomas’ life have left me wondering.

Ironically, had Thomas not sought to publicly clear his name, this unpleasant episode would have been consigned to history. The edition of the Maitland Mercury that contained the woman’s original allegation has not survived.

In 1891 Thomas married his first wife Agnes. The match would likely have been welcomed by Thomas’ father – Agnes was the daughter of a prominent land owner. The couple had three children in quick succession (including my grandfather), but Thomas could not settle to married life and left the family to look for work. He travelled and drank, and became involved in dubious business dealings that led to run-ins with the police. His father bailed him out on at least one occasion, but the humiliation Thomas caused his family was too much for Agnes to bear.

She wrote to Thomas and told him exactly what she thought of him:

‘… the only feeling I have for you now is utter loathing. I can see you now as you are, a dishonest, hypocritical, dishonourable scoundrel.’

Thomas contested Agnes’ first attempt to divorce him, and won. But as far as Agnes was concerned, the damage was done. She forbade Thomas to return to the family home.

‘Father & the boys are so enraged with your wrong doing that I would not answer for the consequences if you … [came] near Glen Barra. When I think how my life has been blighted by you & the pain & worry so many dear ones have had to bear through your bad conduct, it is sometimes more than I can endure.’

Banished from his home in Tamworth, Thomas travelled to Queensland where he met an itinerant domestic servant named Mary Cunningham. Thomas did not tell Mary he was married until well into their relationship. In early 1899 Mary informed Thomas (by letter) that she was ‘in child to him’. Thomas visited Mary once more – just before the child was born – but that was the last time she saw him.

Anger and resentment likely motivated Mary to appear as a witness in Agnes’ second attempt to divorce Thomas. With Mary’s help, Agnes’ petition for divorce – on the grounds of adultery – was successful.

But Thomas’ relationship woes were not over. In 1902 he married single mother Sarah Mackay and had two children with her. Although that marriage lasted longer than his previous relationships, Sarah eventually divorced Thomas on the grounds of desertion.

When Thomas died alone in a mental hospital in Sydney in 1931 he had been estranged from his families for some time. His grave remains unmarked; emblematic of the low regard in which Thomas was held by his families. Ground left bare in the hope that Thomas’ memory might also be erased from the family’s history.

Short Bibliography:

In addition to numerous birth, death & marriage records, newspaper articles etc, Thomas and Agnes’ two divorce files provided illuminating details:

- Divorce of Agnes McLean and Thomas Ross McLean, 1899, No. 3201, Supreme Court of New South Wales, New South Wales Government State Archives and Records, Divorce Records Index 1873-1923, INX-16-7413.

- Divorce of Agnes Maclean and Thomas Ross Maclean, 1901, No. 3965, Supreme Court of New South Wales, New South Wales Government State Archives and Records, Divorce Records Index, INX-16-6817.